Drilling of world’s deepest offshore oil and gas well planned for Colombia this year

(Bloomberg) – The oil and gas industry is pushing the limits of offshore exploration with plans to drill a record-setting deepwater well in Colombia within months.

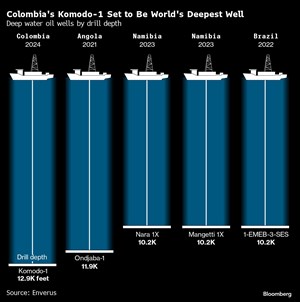

Occidental Petroleum Corp. and Ecopetrol SA are gearing up to plumb the depths of Colombia’s Caribbean waters in search of oil and gas. The plan is to drill the Komodo-1 well before the year is out in seas roughly 3,900 m (close to 13,000 ft) deep. That’s equal to about 10 Empire State Buildings stacked on top of each other and would shatter the current water-depth record holder in Angola.

Oil and gas operators around the world are returning to the deep seas as production growth from North American shale fields slows, forcing companies to expand drilling in other places. SLB, the world’s biggest oil field-services provider, sees the potential for more than $100 billion in commitments to offshore projects for 2024-2025.

“Offshore and deepwater are currently undergoing a remarkable renaissance, driven by the imperatives of energy security, regionalization, and a maturing and disciplined North American shale supply,” James West, an analyst at Evercore ISI, wrote in a note to investors.

Offshore drillers measure wells in two ways: water depth and so-called true vertical depth, or TVD. The first measures the distance between the rig floating on the surface and the spot on the sea floor where drilling will begin. TVD, on the other hand, measures the distance between the rig and the bottom of the well deep inside the Earth.

The effort to break the water-depth record with Komodo-1 has been enabled in part by improved marine-seismic technology that allows exploration at greater depths and distances, Ecopetrol’s offshore chief Elsa Jaimes said during an interview.

Colombia is exploring its huge offshore potential as some onshore reserves begin to peter out, she said. “You have the technology and you also have this huge potential that strengthens our portfolio,” Jaimes added.

Worldwide, more than 40 wells are expected to be drilled this year in seas of least 1,500 m, which would make 2024 the busiest for ultra-deepwater drilling in a decade, according to industry data provider Enverus.

“The fact that we can drill to those depths is what’s driving” the push, said Dai Jones, director of global intelligence at Enverus. Increasing energy demand also is providing a push, he noted.

During the previous decade, deep-sea drillers rapidly expanded rig fleets only to run headlong into the onshore shale revolution and back-to-back oil-market collapses in 2014 and 2016. Some of the world’s biggest offshore drillers resorted to mothballing floating rigs that cost $500 million or more apiece to build.

Deepwater wells will supply as much as one-fourth of global oil output by the end of this decade, compared with about 20% today, according to SLB.

“We are seeing customers going deeper and deeper to more challenging environments,” Wallace Pescarini, president of SLB’s Offshore Atlantic business, said in a phone interview. “It’s natural that the easiest to tap is behind us. So now the new frontiers are a little deeper and a little bit higher pressure.”

While the total cost of offshore exploration is much higher than shale drilling, the potential payouts are massive, longer lasting and more insulated from shifting political and regulatory regimes, according to Enverus’ Jones. Relative to shale, however, the risk of drilling a so-called dry hole — industry jargon for failing to strike oil — is exponentially higher in the ocean.